Return-Oriented Programming (ROP) is not a new concept, yet it remains one of the most sophisticated and challenging exploitation techniques in modern cybersecurity. 💡

Born from the need to bypass fundamental defenses like Data Execution Prevention (DEP), ROP transformed simple stack smashing into a Turing-complete attack vector.

Instead of injecting malicious code, ROP attackers chain together small, existing instruction sequences—called “gadgets”—that end in a return instruction.

By carefully manipulating the stack, the attacker can hijack the program’s control flow to execute arbitrary logic, all while using only legitimate code from the program or its libraries.

This technique is particularly insidious because it subverts the very mechanisms designed to protect systems.

The assembly language level is where ROP operates, making it a low-level, highly effective threat.

Understanding ROP prevention requires a deep dive into how the CPU executes instructions and manages the call stack.

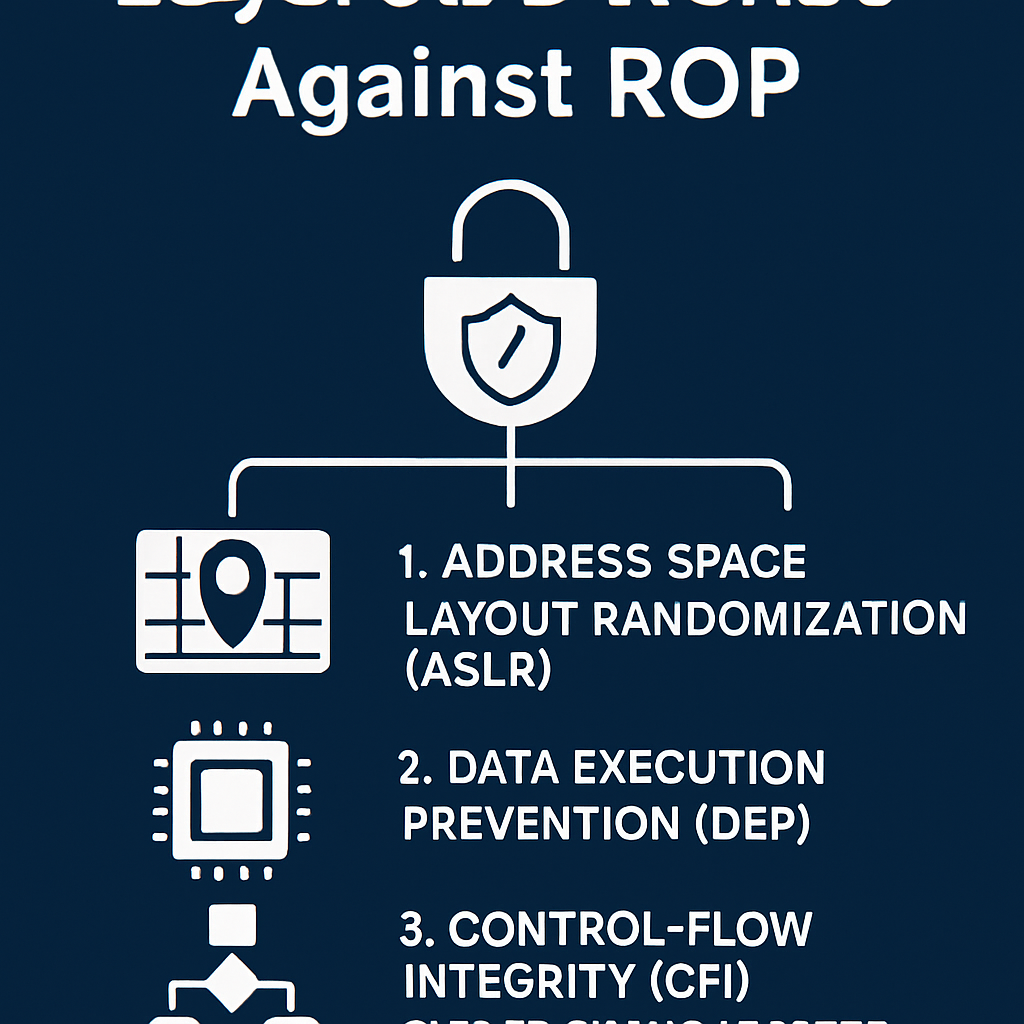

While initial mitigations like Address Space Layout Randomization (ASLR) and DEP provided significant hurdles, determined attackers have developed techniques to bypass them, leading to an arms race in system security.

This article explores the advanced assembly security techniques—from Control-Flow Integrity (CFI) to hardware-assisted protections—that are essential for defending against the next generation of ROP attacks.

We will move beyond the basics to examine the cutting-edge defenses that are redefining secure system architecture.

Section 1: The Anatomy of a ROP Chain 🤓

To defend against ROP, we must first understand its construction.

A ROP attack is fundamentally a chain of execution built by linking “gadgets.”

A gadget is a sequence of one or more machine instructions that already exists within the program’s code base, typically ending with a ret instruction.

The attacker’s goal is to overwrite the return address on the stack with the address of the first gadget.

When the function returns, execution jumps to this gadget.

The gadget performs its small task (e.g., popping a value into a register, performing an arithmetic operation), and the final ret instruction is executed.

Crucially, the attacker has also populated the stack with the addresses of subsequent gadgets.

The ret instruction pops the next address off the stack and jumps to it, effectively making the stack itself the instruction pointer for the ROP chain.

By carefully selecting and ordering these gadgets, an attacker can perform complex operations, such as calling system functions like execve to spawn a shell.

The power of ROP lies in its ability to construct any desired behavior from the existing code, making it a “code reuse” attack.

The challenge for defenders is that ROP chains look like legitimate program execution at the instruction level.

They only become malicious when viewed as a sequence of high-level operations.

This is why traditional security measures, which focus on preventing code injection or randomizing memory locations, often fall short.

The attacker is not injecting code; they are simply repurposing it.

This is a key distinction that drives the need for more sophisticated, control-flow-aware security mechanisms.

The complexity of finding and chaining gadgets has led to automated tools, but the core principle remains the same: hijack the return address and control the stack.

Understanding the stack frame and the role of the base pointer (EBP/RBP) and stack pointer (ESP/RSP) is paramount for both exploit development and defense.

Section 2: Traditional Mitigations and Their Limitations 📌

For years, the primary defenses against memory corruption exploits, including ROP, have been DEP, ASLR, and Stack Canaries.

While effective against simpler attacks, they are no longer sufficient on their own.

Data Execution Prevention (DEP)

DEP, or the NX (No-Execute) bit, marks memory pages as non-executable.

This prevents an attacker from injecting and running code in data segments like the stack or heap.

DEP was the catalyst for ROP, as attackers could no longer execute their own code and were forced to reuse existing code.

ROP chains are specifically designed to bypass DEP by executing only code that resides in the program’s legitimate, executable memory sections.

Address Space Layout Randomization (ASLR)

ASLR randomizes the base addresses of key memory regions (like the stack, heap, and libraries) every time a program runs.

This makes it difficult for an attacker to predict the exact location of the gadgets they need.

However, ASLR is often defeated through information leaks.

If an attacker can find a single pointer to a known library function, they can calculate the base address of that library and thus the location of all its gadgets.

Furthermore, partial ASLR implementations or low-entropy randomization can be brute-forced, especially in 32-bit systems.

The effectiveness of ASLR is directly tied to the entropy of the randomization, which is often compromised by side-channel attacks or memory disclosure vulnerabilities.

Stack Canaries

Stack canaries are secret values placed on the stack before the return address.

Before a function returns, the program checks if the canary value has been modified.

If it has, a buffer overflow is detected, and the program is terminated.

While highly effective against simple stack-based buffer overflows, canaries only protect the return address immediately following them.

ROP attacks can sometimes bypass canaries by exploiting vulnerabilities that don’t involve overwriting the canary, or by leaking the canary value itself.

For a deeper dive into how ROP can still be dangerous against modern defenses, read this paper: ROP is Still Dangerous: Breaking Modern Defenses.

| Mitigation | Primary Defense Target | ROP Bypass Method |

|---|---|---|

| DEP (NX Bit) | Code Injection | Reuses existing executable code (gadgets) |

| ASLR | Predictable Addresses | Information leaks or brute-force attacks |

| Stack Canaries | Stack Buffer Overflows | Non-stack-based overflows or canary value leaks |

Section 3: Advanced Control-Flow Integrity (CFI) 🛠️

The limitations of traditional defenses have led to the development of Control-Flow Integrity (CFI), a paradigm shift in memory safety.

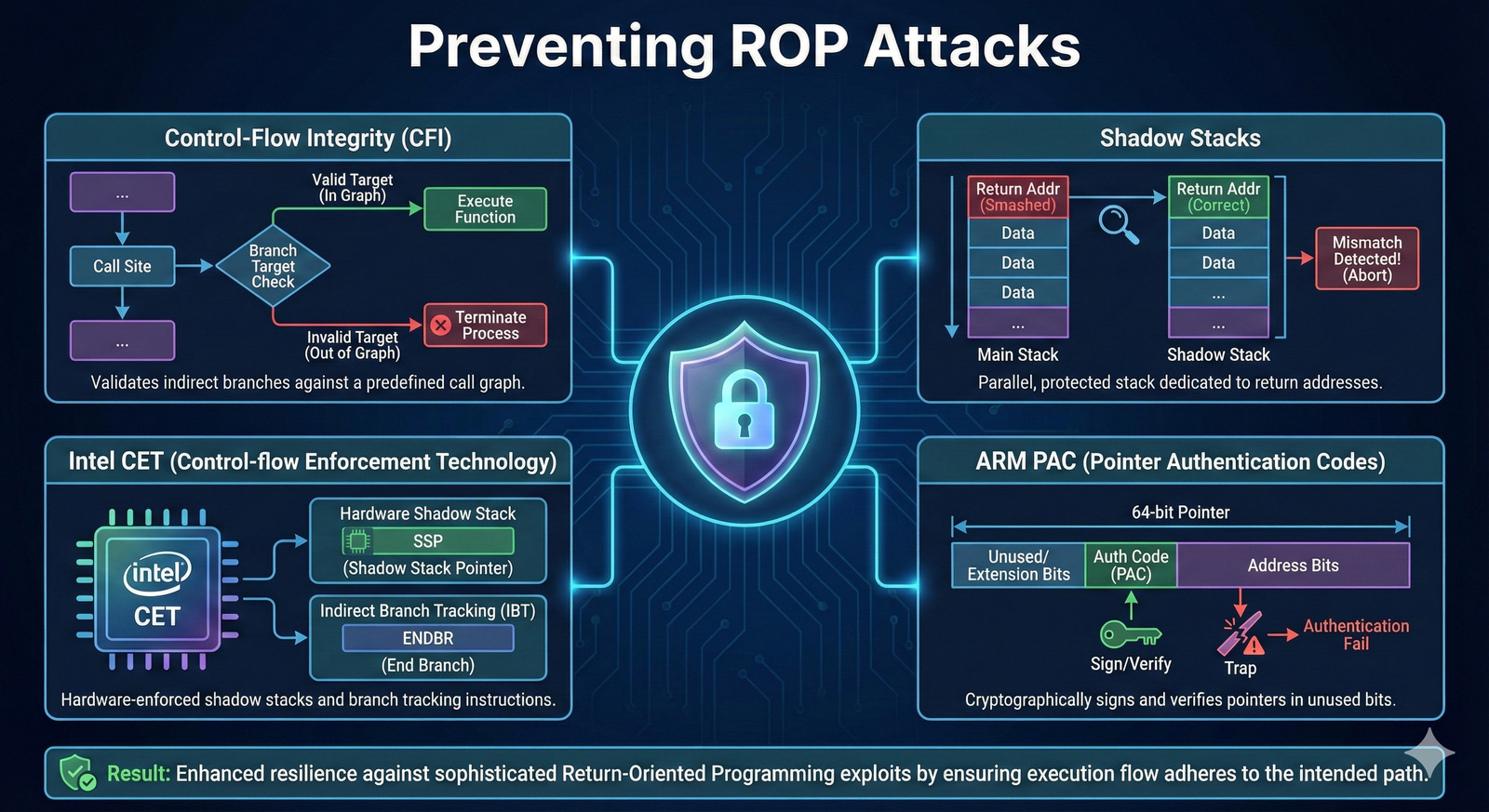

CFI aims to ensure that a program’s execution flow only follows paths that were intended by the original program logic.

This is a direct countermeasure to ROP, which is fundamentally a control-flow hijacking attack.

CFI is typically implemented by instrumenting the program’s binary during compilation or linking.

It works by creating a “control-flow graph” (CFG) that maps all legitimate transfers of control (calls, jumps, returns).

At runtime, before any control-flow transfer instruction is executed, the CFI mechanism checks if the target address is a valid destination according to the pre-computed CFG.

The challenge with CFI is achieving a balance between security and performance, as overly strict CFI can introduce significant overhead.

Backward-Edge CFI (Protecting Returns)

This is the most direct defense against ROP.

Since ROP relies on hijacking the ret instruction, backward-edge CFI focuses on ensuring that a function returns to its legitimate caller.

The most common implementation is the Shadow Stack.

A Shadow Stack is a separate, protected stack that mirrors the return addresses pushed onto the normal data stack.

When a function is called, the return address is pushed onto both the normal stack and the shadow stack.

When the function returns, the address popped from the normal stack is compared against the address popped from the shadow stack.

If they do not match, a ROP attack is detected, and the program is halted.

The shadow stack is protected from the attacker’s write operations, making it an extremely robust defense.

Forward-Edge CFI (Protecting Calls and Jumps)

While backward-edge CFI stops ROP chains built with ret instructions, attackers can also use indirect calls (call *reg) and indirect jumps (jmp *reg) to build “Jump-Oriented Programming” (JOP) or “Call-Oriented Programming” (COP) chains.

Forward-edge CFI ensures that the target of an indirect call or jump is a valid entry point for the program.

This is a more complex problem, as a single indirect call might legitimately target hundreds of different functions (e.g., virtual method calls in C++).

Fine-grained CFI, which attempts to restrict targets to the smallest possible set, offers the highest security but is the most challenging to implement without false positives.

For an example of fine-grained CFI in the Linux kernel, see this Black Hat paper: DROP THE ROP: Fine-grained Control-flow Integrity for the Linux Kernel.

Section 4: Hardware-Assisted ROP Prevention 🛡️

The performance overhead of software-based CFI has driven the industry toward hardware-assisted solutions, which offer robust security with minimal performance impact.

These technologies are integrated directly into the CPU architecture, providing a root of trust that is difficult for software exploits to compromise.

Intel Control-Flow Enforcement Technology (CET)

Intel’s CET is a major hardware-based initiative to combat ROP and JOP.

It introduces two key features:

- Shadow Stack: A hardware-enforced, protected stack for return addresses, directly implementing backward-edge CFI. The CPU ensures that only

callinstructions can push to the shadow stack and onlyretinstructions can pop from it. This makes it virtually impossible for a ROP attacker to manipulate the return addresses. - Indirect Branch Tracking (IBT): A mechanism for forward-edge CFI. It ensures that indirect jumps and calls only land on valid “landing pads” in the code, which are marked with a special instruction. Any jump to an unmarked location is blocked by the hardware.

Microsoft has integrated this technology into Windows, extending hardware-enforced stack protection to the kernel. You can read more about it here: Kernel Mode Hardware-enforced Stack Protection.

ARM Pointer Authentication Codes (PAC)

ARM’s architecture uses Pointer Authentication Codes (PACs) to protect return addresses and other sensitive pointers.

Before a return address is pushed onto the stack, a cryptographic hash (the PAC) is generated based on the pointer value, a secret key, and a context value, and then embedded into the pointer itself.

Before the address is used for a return, the CPU verifies the PAC.

If the attacker modifies the return address, the PAC verification will fail, and the attack is thwarted.

This provides a strong, cryptographic integrity check on the control flow.

PAC is a versatile mechanism that can be used to protect various pointers, not just return addresses, making it a powerful primitive for memory safety.

A detailed look at how PAC is used to create an authenticated call stack can be found in this paper: PACStack: an Authenticated Call Stack.

Section 5: The Developer’s Role and Future Outlook 🚀

While hardware and operating system defenses are crucial, the first line of defense remains secure coding practices.

A vulnerability that allows a buffer overflow is the necessary precursor to any ROP attack.

Developers must prioritize memory-safe languages or rigorously use safe functions in C/C++.

Best Practices for Secure Assembly-Level Programming

The following practices are essential for building robust software:

- Use Safe Libraries: Avoid legacy, unsafe functions like

strcpy,gets, andsprintf. Use safer alternatives likestrncpy,fgets, andsnprintf. - Compiler Flags: Always compile with modern exploit mitigation flags enabled (e.g.,

-fstack-protector-all,-Wformat-security,-D_FORTIFY_SOURCE=2). - Code Audits: Regularly perform static and dynamic analysis to identify potential buffer overflows and other memory corruption vulnerabilities.

- Minimize Gadgets: While difficult, reducing the number of available ROP gadgets in a binary can raise the bar for attackers. Techniques like binary hardening and code obfuscation can help.

- Adopt CFI: Integrate compiler-based CFI solutions like LLVM’s CFI or GCC’s

-fsanitize=cfiinto the build process.

The future of ROP prevention is moving towards full, hardware-enforced CFI.

As Intel CET and ARM PAC become ubiquitous, the cost and complexity of mounting a successful ROP attack will increase dramatically.

However, the security landscape is a constant battle.

Researchers are already exploring ways to bypass or degrade these new hardware protections, such as “Blind ROP” or exploiting side-channel attacks to leak PAC keys.

The next frontier will likely involve probabilistic defenses and micro-randomization techniques that operate at an even finer granularity than current ASLR implementations.

For a look at how to survive the new hardware-assisted enforcement, check out this resource:

How to Survive the Hardware-assisted Control-flow Integrity Enforcement.

The ultimate goal is to make the exploitation of memory corruption vulnerabilities economically unviable for attackers.

Conclusion: Securing the Assembly Frontier 🌐

ROP attacks represent the pinnacle of memory exploitation, demonstrating that simply preventing code injection is insufficient.

The shift from traditional mitigations like DEP and ASLR to advanced techniques like Control-Flow Integrity and hardware-assisted Shadow Stacks marks a critical evolution in system security.

By understanding the assembly-level mechanics of ROP and implementing a layered defense strategy—combining secure coding practices, compiler-based mitigations, and cutting-edge hardware features—we can significantly raise the bar against even the most determined adversaries.

The battle against ROP is a testament to the continuous innovation required to secure the digital world.

Staying ahead means embracing these advanced techniques and never underestimating the ingenuity of the attacker.

This layered approach ensures that even if one defense is bypassed, others remain to protect the system’s integrity.

The future of software security is inextricably linked to the hardware, where the most robust defenses are now being forged.

The ongoing research into new attack vectors, such as Functional Oriented Programming (FOP), highlights the need for constant vigilance and adaptation in the security community.

The final layer of defense is always the informed and diligent developer.