The adoption of Docker and containerization has revolutionized software deployment, offering unparalleled speed, portability, and efficiency.

However, this rapid shift has also introduced a new and complex attack surface.

A single misconfiguration in a Dockerfile or a running container can expose your entire host system, leading to catastrophic security breaches.

Securing your containers is not a one-time task but a continuous, multi-layered process that spans the entire development lifecycle, from image creation to runtime enforcement.

This comprehensive guide details the essential Docker security best practices you must implement to build an unbreakable container environment in production.

Phase 1: Securing the Image Build Process

The foundation of container security begins with the image itself.

A vulnerable image is a ticking time bomb, regardless of how well the runtime environment is secured.

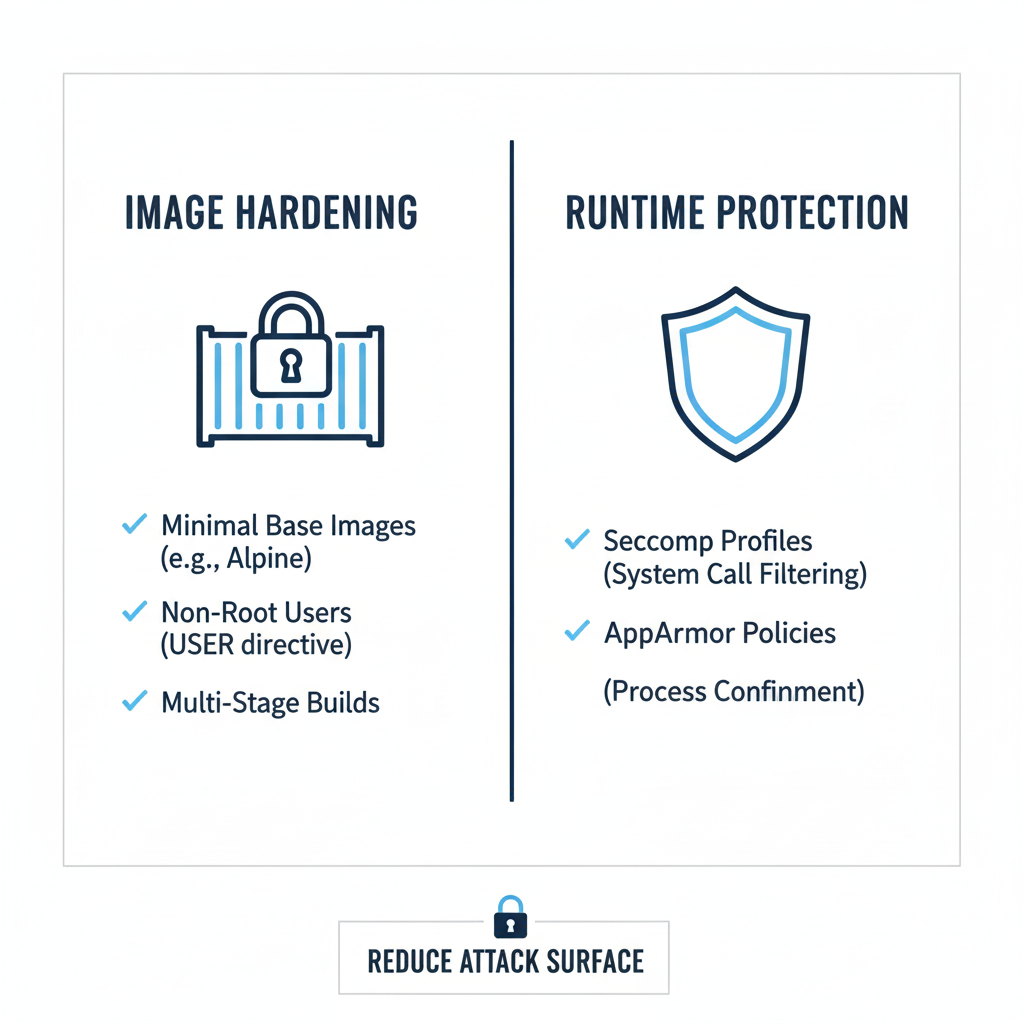

1. Use Minimal and Trusted Base Images

The base image is the starting point for your entire application.

Choosing a minimal and trusted base image is the single most effective way to reduce the attack surface.

Minimalism is Key

- Opt for minimal distributions like Alpine Linux or Distroless images.

- These images contain only the essential runtime components, drastically reducing the number of packages, libraries, and potential vulnerabilities.

- Alpine, based on musl libc and BusyBox, is significantly smaller than traditional distributions.

- Distroless images, provided by Google, go a step further by containing only your application and its runtime dependencies, with no shell, package manager, or other utilities that an attacker could exploit.

- A smaller image size also translates to faster build and deployment times.

Trust the Source

- Always pull base images from trusted, verified sources like Docker Hub’s official repositories or a private, secured registry.

- Avoid using images with unknown origins, as they may contain hidden backdoors or outdated, vulnerable software.

- Implement a strict policy that only allows images from approved sources.

Pin Image Versions

- Never use the

:latesttag in production. - Always pin your base images to a specific, immutable digest or a major/minor version (e.g.,

node:18-alpine). - This prevents unexpected changes and ensures reproducibility, which is vital for security audits and rollbacks.

2. Run as a Non-Root User

Running processes as the root user inside a container is one of the most critical security mistakes.

If an attacker manages to escape the container, they will have root privileges on the host system.

The USER Instruction

- Use the

USERinstruction in your Dockerfile to switch to a non-root user after installing dependencies. - This is a simple yet powerful defense.

User Namespaces

- For an extra layer of defense, enable User Namespaces (userns-remap) on the Docker daemon.

- This maps the container’s root user to an unprivileged user on the host, effectively isolating the container’s root from the host’s root.

- This significantly mitigates the impact of a container breakout.

3. Implement Multi-Stage Builds

Multi-stage builds are a powerful technique to ensure your final production image contains only the necessary runtime artifacts and nothing else.

This practice is a cornerstone of the “build once, deploy many” philosophy.

- Use one stage for building the application (compiling code, installing development dependencies, running tests) and a separate, minimal stage for the final runtime image.

- This eliminates build tools, source code, test data, and unnecessary dependencies from the production environment, significantly reducing the attack surface and image size.

- For example, a Go application can be compiled in a large Go image, and only the final static binary is copied into a tiny Alpine or Distroless image.

4. Scan Images for Vulnerabilities

Vulnerability scanning should be an integral part of your Continuous Integration/Continuous Deployment (CI/CD) pipeline.

This is where you “shift left” your security efforts.

Automated Scanning

- Integrate tools like Trivy, Clair, or Snyk to automatically scan images for known Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVEs) before they are pushed to the registry.

- These tools analyze the image layers and compare them against public vulnerability databases.

Policy Enforcement

- Configure your registry (e.g., AWS ECR, Docker Hub) to block deployment of images that fail to meet a minimum security threshold (e.g., images with critical or high-severity vulnerabilities).

- This gate prevents insecure images from ever reaching production.

Continuous Monitoring

- Vulnerabilities are discovered daily.

- Even a clean image can become vulnerable overnight.

- Implement continuous scanning of images already in your registry and running in production to catch newly disclosed CVEs.

Phase 2: Hardening the Container Runtime

Even a perfectly built image can be compromised if the runtime environment is not properly secured.

These practices focus on limiting the container’s capabilities and access to the host system.

5. Limit Container Capabilities

By default, Docker drops most Linux capabilities, but it still retains a few that are often unnecessary for a typical application.

The principle of least privilege dictates that you should drop all capabilities and only add back the ones your application explicitly needs.

Drop All, Add Back

- Use the

--cap-drop ALLflag and then selectively add back only the required capabilities with--cap-add. - For example, a web server might only need

NET_BIND_SERVICEto bind to a port below 1024.

Avoid --privileged

- Never run a container with the

--privilegedflag in production. - This grants the container all capabilities and direct access to host devices, essentially removing all security boundaries.

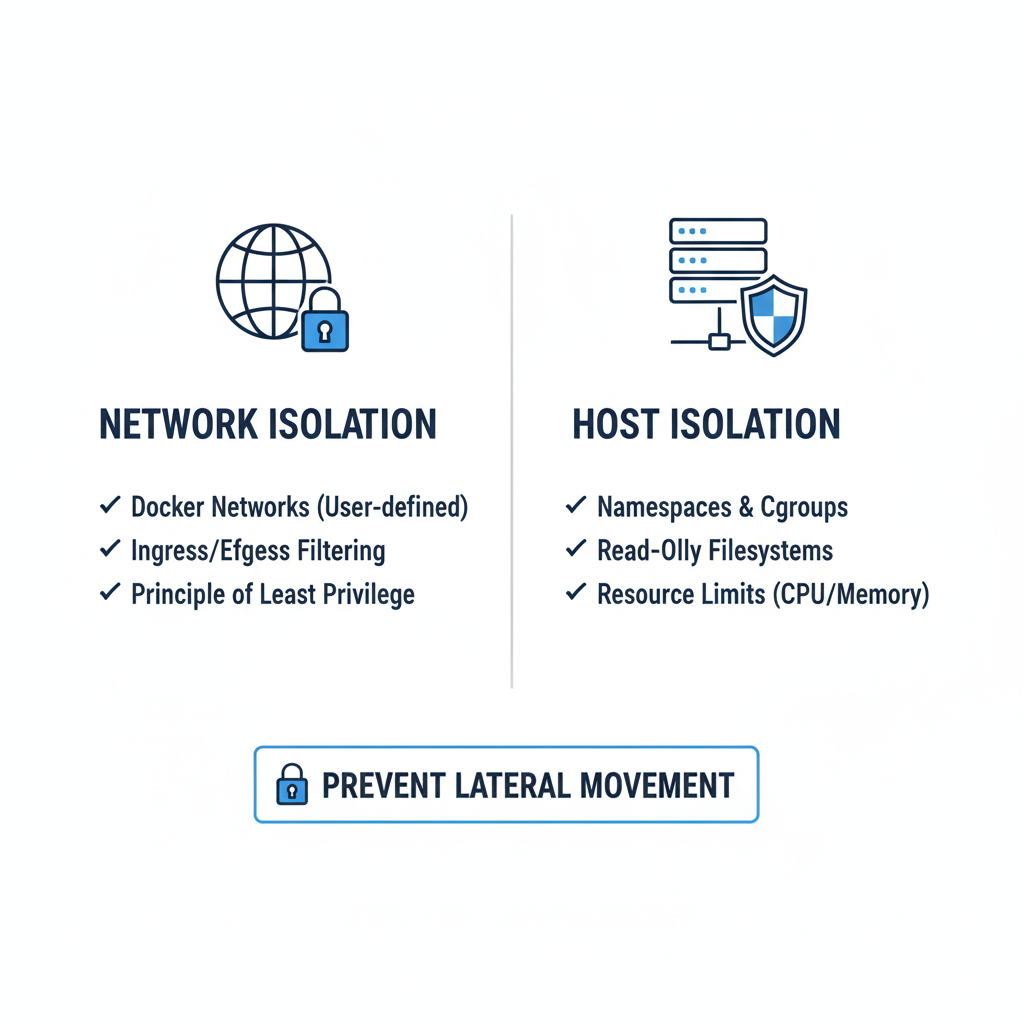

6. Set Filesystem and Volumes to Read-Only

Most applications do not need to write to their own filesystem after they start.

Running a container with a read-only root filesystem is a powerful defense against malware and tampering.

The --read-only Flag

- Use the

--read-onlyflag withdocker run. - This prevents an attacker from modifying the application binary or configuration files.

- If the application needs to write temporary data (e.g., logs, cache), use the

--tmpfsflag to mount a temporary in-memory filesystem for those specific directories.

Read-Only Volumes

- For persistent data, mount volumes as read-only (

:ro) unless the application absolutely requires write access to that specific volume. - This protects configuration and data volumes from being corrupted or exfiltrated.

7. Secure Secrets Management

Hardcoding sensitive data like API keys, database credentials, or private keys directly into the Dockerfile or environment variables is a major security risk.

This is a common failure point in many container deployments.

Use Dedicated Secrets Managers

- Utilize dedicated secrets management solutions like Docker Secrets (for Docker Swarm), Kubernetes Secrets, or external vaults like HashiCorp Vault or AWS Secrets Manager.

- These tools inject secrets into the container’s memory at runtime, preventing them from being exposed in environment variables or image layers.

Avoid Environment Variables

- Environment variables are easily exposed via

docker inspectand are persisted in image layers. - Use them only for non-sensitive configuration data.

- For Kubernetes, use

Secretobjects and mount them as files into the container, which is generally safer than using environment variables.

8. Implement Resource Limits

Uncontrolled resource consumption can lead to Denial of Service (DoS) attacks, where a single compromised container starves the host or other containers of resources.

This is a critical operational security measure.

Limit CPU and Memory

- Always set limits for CPU and memory using flags like

--cpusand--memory. - This ensures that a runaway process in one container cannot impact the stability of the entire host or other critical services.

Limit File Descriptors and Processes

- Use

--ulimitto limit the number of open file descriptors and processes a container can spawn, mitigating fork-bomb and resource exhaustion attacks. - These limits are essential for maintaining the health and stability of the host system.

Phase 3: Network and Host Isolation

The final layer of defense involves isolating the container from the host and from other containers on the network.

A well-segmented network is crucial for minimizing the lateral movement of an attacker.

9. Isolate Containers with Custom Networks

By default, Docker enables Inter-Container Connectivity (ICC), allowing all containers on the same bridge network to communicate freely.

This is often unnecessary and increases the blast radius of a breach.

Custom Bridge Networks

- Create custom bridge networks and only connect containers that explicitly need to communicate.

- This provides a default deny posture for network traffic between services.

- For example, a database container should only be accessible from its corresponding application container, not from a public-facing web container.

Network Policies (Kubernetes)

- In a Kubernetes environment, use Network Policies to define granular, least-privilege rules for how Pods can communicate with each other and external endpoints.

- This is the gold standard for container network segmentation.

10. Secure the Docker Daemon and Host

The Docker daemon is the control plane for your entire container environment.

Compromising the daemon means compromising the host.

Daemon Socket Access

- Never expose the Docker daemon socket (

/var/run/docker.sock) to other containers or over a TCP port without strong authentication and TLS encryption. - Granting access to this socket is equivalent to granting root access to the host.

Keep Host and Docker Updated

- Regularly update the host operating system, kernel, and the Docker Engine itself.

- This is crucial for patching kernel-level vulnerabilities (like Dirty COW or Leaky Vessels) that could allow a container escape.

- Use automated patching and reboot strategies to minimize downtime.

Use a Dedicated Host

- Run the Docker daemon on a dedicated host that does not run other critical services.

- Consider using a minimal OS like CoreOS or RancherOS that is optimized for running containers.

11. Implement Runtime Security with LSMs

Linux Security Modules (LSMs) provide mandatory access control mechanisms that can further restrict what a container can do, even if an attacker gains root access inside the container.

Seccomp

- The default Seccomp profile drops over 40 syscalls, significantly reducing the attack surface.

- Customize this profile to drop even more syscalls that your application does not need.

AppArmor/SELinux

- Use AppArmor (for Debian/Ubuntu) or SELinux (for Red Hat/CentOS) to enforce mandatory access control policies on containers, restricting their ability to interact with the host kernel and filesystem.

- These tools provide a powerful defense-in-depth layer.

Phase 4: Advanced Defense and Automation

To achieve true production-grade security, you must move beyond static configuration and embrace dynamic, automated security controls.

12. Continuous Monitoring and Behavioral Analysis

Static security checks are not enough.

You need to monitor the actual behavior of your containers at runtime to detect anomalies.

Behavioral Monitoring

- Use tools like Falco or Tetragon to monitor container activity against a set of expected behaviors.

- For example, if a web server container suddenly tries to spawn a shell or access a sensitive host file, it should trigger an immediate alert and potentially an automated response.

Log Aggregation

- Centralize all container logs (application, system, and security) into a Security Information and Event Management (SIEM) system.

- This allows for correlation of events and faster incident response.

13. Read-Only Root Filesystem and Volume Security

Revisiting the read-only principle, this is a simple configuration that yields massive security benefits.

Immutable Infrastructure

- Treat your containers as immutable.

- Once built, they should never be modified.

- The

--read-onlyflag enforces this principle at the filesystem level.

Volume Permissions

- When mounting volumes, ensure that the permissions are set correctly.

- The container user should only have the minimum required permissions on the mounted volume.

- Avoid mounting the entire host filesystem or sensitive directories like

/procor/sysunless absolutely necessary and with extreme caution.

14. Harden the Dockerfile with Linter and Scanners

Integrate tools that check your Dockerfile for security anti-patterns before the image is even built.

Dockerfile Linters

- Tools like Hadolint can check for common mistakes such as using

ADDinstead ofCOPY, exposing sensitive ports unnecessarily, or runningapt-get updatewithoutapt-get clean.

Minimize Layers

- While Docker’s build cache is useful, each instruction in a Dockerfile creates a new layer.

- Minimize the number of layers, especially those that contain sensitive information, as layers are immutable and can be inspected.

Conclusion: Security as Code

In the world of containerization, security must be treated as code—defined, automated, and version-controlled.

By meticulously applying these best practices across the image build, runtime, and network layers, you can significantly reduce your attack surface and build a resilient, production-ready container environment.

The goal is to move beyond mere compliance and embed a culture of security into every aspect of your container lifecycle.

An unbreakable container is one that is minimal, runs with the least privilege, and is continuously monitored for anomalous behavior.

The transition to containers offers immense benefits, but it demands a renewed commitment to security.

By adopting these best practices, you transform Docker from a potential vulnerability into a powerful security boundary, ensuring your applications are not just fast and portable, but fundamentally secure.

| Security Phase | Best Practice | Key Tool/Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Image Build | Use Minimal Base Images | Alpine, Distroless |

| Image Build | Run as Non-Root User | USER instruction, User Namespaces |

| Image Build | Vulnerability Scanning | Trivy, Clair, Snyk |

| Runtime Hardening | Least Privilege Capabilities | --cap-drop ALL |

| Runtime Hardening | Read-Only Filesystem | --read-only flag |

| Runtime Hardening | Secure Secrets Management | Docker Secrets, HashiCorp Vault |

| Isolation | Network Segmentation | Custom Bridge Networks, Network Policies |

| Isolation | Host Protection | Seccomp, AppArmor, SELinux |