For nearly six decades, the semiconductor industry has marched to the relentless beat of a single drum: Moore’s Law.

This observation, made by Intel co-founder Gordon Moore in 1965, famously predicted that the number of transistors on a microchip would double approximately every two years. 🤓

This exponential growth fueled the digital revolution, giving us smartphones more powerful than the supercomputers of yesteryear.

However, as we approach atomic-scale dimensions, the physics of silicon are pushing back.

The era of easily shrinking transistors to get “free” performance gains is effectively over. 🛑

But does this mean the end of computing advancement?

Absolutely not.

We are transitioning from an era of “more” to an era of “smarter” and “different.”

The future of microprocessor scaling is no longer just about shrinking gates; it is about architectural innovation, novel materials, and radical new computing paradigms. 💡

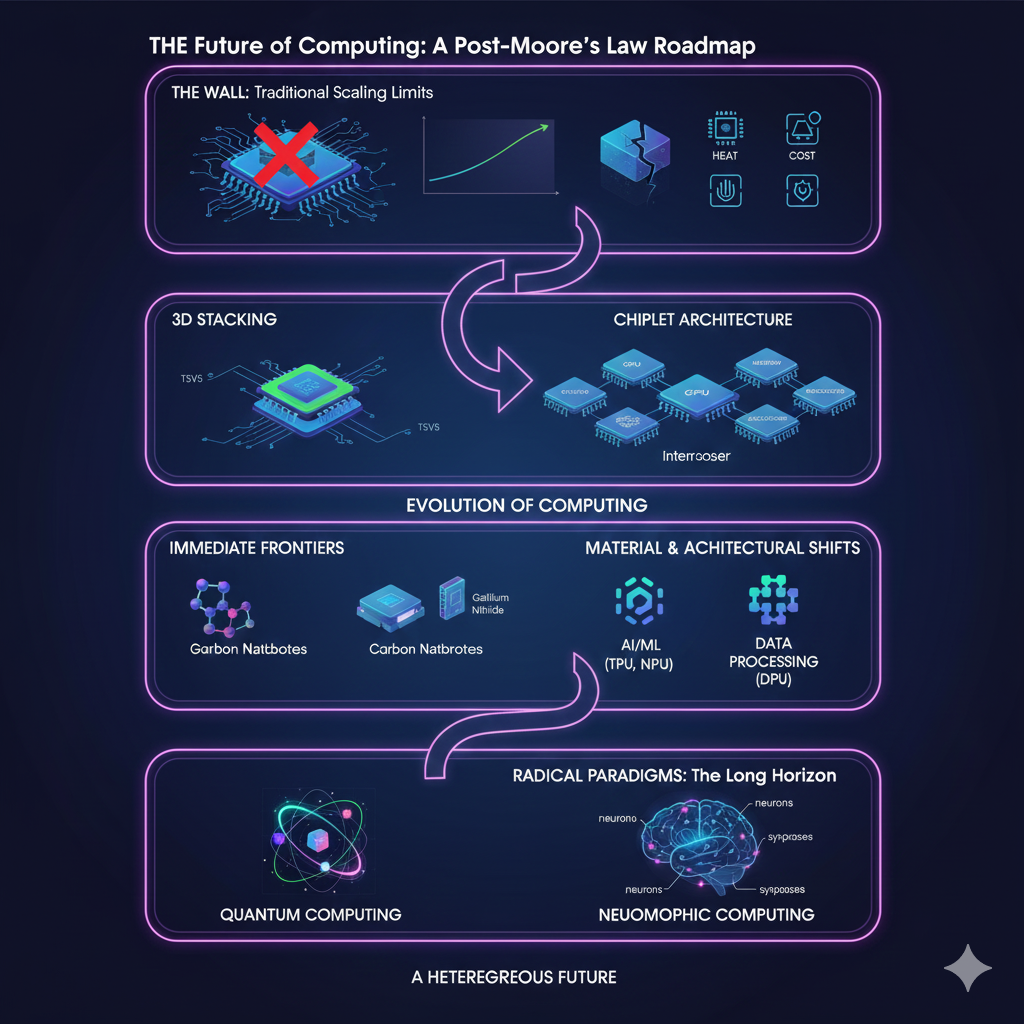

The Wall: Why Traditional Scaling is Stalling

To understand the future, we must understand why the old ways are failing.

Traditionally, we relied on Dennard Scaling, which stated that as transistors got smaller, their power density stayed constant, meaning faster chips didn’t necessarily use more energy overall.

That symbiotic relationship broke down over a decade ago. 📉

Today, packing billions of tiny transistors onto a thumbnail-sized piece of silicon creates immense heat challenges.

Furthermore, the economic reality is biting harder than the physical one.

Building the leading-edge fabrication plants (fabs) required to manufacture 3-nanometer or 2-nanometer chips costs tens of billions of dollars.

Only a handful of companies on Earth can afford this investment. 💰

We have hit a point of diminishing returns where simply shrinking features is no longer the most viable path forward.

According to IEEE Spectrum analysis, the consensus among experts is that while transistor counts may still increase, the associated performance gains and cost reductions have slowed dramatically.

“No exponential is forever—but ‘forever’ can be delayed!”

— Gordon Moore

“More Than Moore”: The Immediate Solutions

The industry’s immediate response to the slowing of traditional scaling is a strategy often called “More than Moore.”

If we cannot make the transistors on a single 2D plane much smaller, we must find other ways to increase system performance.

This involves rethinking how chips are packaged and connected. 🧩

1. Going Vertical: 3D Stacking and Advanced Packaging

Think of a sprawling suburban city defined by urban sprawl; that is a traditional 2D chip.

Now, imagine a dense metropolis filled with skyscrapers; that is 3D stacking.

Engineers are now stacking memory layers directly on top of logic layers using advanced techniques like through-silicon vias (TSVs).

This drastically reduces the distance data needs to travel, improving speed and reducing power consumption. ⚡

2. The Chiplet Revolution

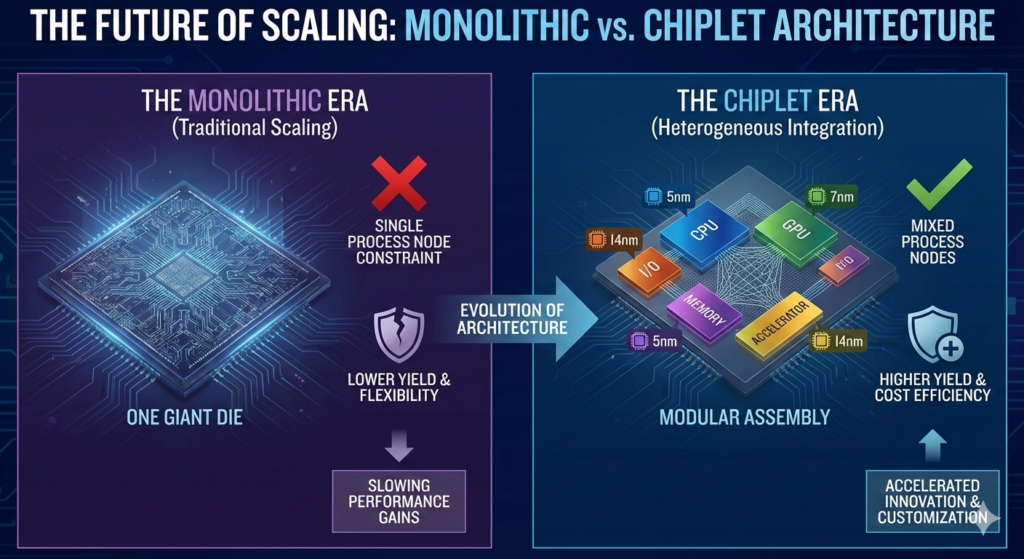

Perhaps the most significant shift currently underway is the move toward “chiplets.”

Instead of manufacturing one gigantic, complex brain on a single piece of silicon (a monolithic die), manufacturers are breaking the design into smaller, functional blocks.

These blocks, or chiplets—one for graphics, one for processing cores, one for I/O—are manufactured separately and then stitched together using advanced packaging technologies.

This approach allows manufacturers to mix and match process technologies, using cutting-edge nodes for critical compute cores while using older, cheaper nodes for less demanding functions. 📌

(Infographic visualization: Monolithic vs. Chiplet Architecture)

| Feature | Monolithic Design | Chiplet Design |

|---|---|---|

| Manufacturing Complexity | High (One giant die) | Lower (Smaller individual dies) |

| Yield Rates | Lower (One defect ruins the whole chip) | Higher (Defects only ruin small pieces) |

| Cost Flexibility | Low (Must use one process node) | High (Mix and match nodes) |

| Time to Market | Slower | Faster (Modular assembly) |

Beyond Silicon: New Materials

Silicon has had an amazing run, but it is starting to show its age.

As transistors shrink, silicon struggles to control the flow of electrons effectively, leading to “leakage” and inefficiency.

Researchers are actively hunting for successors. 🕵️♀️

- Graphene: Often called a “wonder material,” graphene is a single layer of carbon atoms arranged in a hexagonal lattice; it is incredibly conductive and strong, but manufacturing it at scale for semiconductors remains a massive challenge.

- Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs): These are tiny cylinders of carbon that exhibit extraordinary electrical properties. Researchers at institutions like MIT have already demonstrated working microprocessors built entirely from carbon nanotube transistors, proving they are a viable, energy-efficient alternative to silicon.

- Gallium Nitride (GaN): Already popular in power chargers, GaN handles higher voltages and temperatures better than silicon, making it ideal for specific power and radio frequency applications.

You can read more about the cutting-edge research into 2D materials at MIT News.

Architectural Specialization: The Rise of Accelerators

For decades, we relied on general-purpose Central Processing Units (CPUs) to do everything.

But as specific workloads—like Artificial Intelligence and machine learning—became dominant, we realized CPUs were jacks of all trades but masters of none.

The future is highly specialized. 🧐

We are seeing an explosion in Domain-Specific Architectures (DSAs).

Graphics Processing Units (GPUs) were the first wave, repurposed from gaming to become the workhorses of AI training.

Now we have Tensor Processing Units (TPUs), Neural Processing Units (NPUs), and Data Processing Units (DPUs).

Companies like NVIDIA have thrived by recognizing that accelerated computing—using specialized hardware alongside CPUs—is the only way to handle modern data demands.

“A new golden age for computer architecture has begun.”

— David Patterson and John Hennessy, Turing Award Winners

The Long Horizon: Radical Paradigms

While chiplets and new materials extend the current runway, truly long-term scaling requires breaking away from the classic “von Neumann” architecture that has defined computers for seventy years.

Two major contenders stand out: Quantum and Neuromorphic computing.

1. Quantum Computing

Quantum computing is not just a faster conventional computer; it operates on entirely different physics.

Classical computers use bits (0 or 1).

Quantum computers use qubits, which thanks to superposition, can exist in multiple states simultaneously, allowing them to explore vast computational spaces incredibly quickly for specific types of problems. ⚛️

They won’t replace your laptop for checking email, but they could revolutionize materials science, drug discovery, and complex optimization problems.

Major players like IBM Quantum are rapidly increasing their qubit counts, though error correction remains a significant hurdle.

2. Neuromorphic Computing

If quantum looks to physics for inspiration, neuromorphic computing looks to biology.

The human brain is arguably the most efficient computer in existence, performing complex pattern recognition on roughly 20 watts of power. 🧠

Neuromorphic chips, like Intel’s Loihi, are designed to mimic the brain’s architecture of neurons and synapses.

Instead of shuttling data back and forth between memory and processor (the primary bottleneck in today’s computers), neuromorphic chips commingle processing and memory, leading to massive gains in energy efficiency for AI tasks.

Learn more about these brain-inspired systems at Intel Labs.

Conclusion: The Heterogeneous Future

Is Moore’s Law dead?

If you define it strictly as the doubling of transistors on a 2D plane, it is certainly on life support.

But if you define it by Gordon Moore’s original intent—the continuous exponential increase in computing power at declining costs—it is evolving.

We are entering a heterogeneous future.

The supercomputer of 2035 will likely not be a single massive CPU.

It will be a complex symphony of silicon CPUs, carbon nanotube accelerators, stacked memory, and perhaps a quantum co-processor, all working in concert. 🎻

The free lunch of easy scaling is over, but the banquet of innovation has just begun.

The path forward is harder, more expensive, and requerres deeper physics, but the rewards will be computational capabilities we can currently barely imagine. 🚀